There are many scientific disciplines. However, they’re all subdivisions of the broad philosophical classification of metaphysics. Many atheist scientists have hijacked this ideology to imply that science is a self-contained domain, but it’s a vastly connected discipline with basically everything that can be known.

Formal Sciences

In many ways, the formal sciences are philosophical abstractions:

- Logic

- Mathematics (algebra, statistics, calculus, et al.)

- Decisions theory (aka game theory)

These are more philosophy than science, but they’re so well-ordered that they can exist as being provable.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Given the improbability of our existence, is it strictly random?

- How did consciousness come into existence? What benefit does it give?

- What is the survival benefit of existential questions?

- Can we ever make a computer into a form of life?

- Why does the Riemann hypothesis (the pattern for prime numbers) exist?

- What are the odds of beating a game of Solitaire?

Regarding what people typically think of with the word “science”, it broadly classifies into the physical and life sciences, with the social sciences thrown in as a somewhat “soft science” and the applied sciences actually making the sciences legitimately useful.

All Sciences

One important component representative in all the sciences is that there are two strangely competing forces always at work:

- Everything is maintaining a type of stasis, with constant negative feedback loops that self-corrects anything too far out of range.

- Everything in the universe is decaying at a relatively predictable rate.

In practice, everything is absurdly simple from one perspective, but is vastly complicated in its implementation. This includes science itself.

The sciences end up combining on top of each other:

- Physics is the base.

- Specific interactions between elements in physics becomes Chemistry.

- The physical world around us, along with its physical interactions, is Earth Science.

- Earth science’s subdivisions as Geology, Oceanography, and Meteorology.

- Everything about physics that isn’t earth science is Astronomy.

- Specific chemistry pertaining to life is Biochemistry, itself a subdomain of Biology

- Biochemistry’s subdivisions as Microbiology, Botany, and Zoology.

- The Social Sciences are subdivisions of biochemistry regarding human behavior.

- Earth science as applied to biochemistry is Ecology.

To save time on learning for the sake of certainty, it’s vitally important to hammer out your metaphysics before diving into science:

- If there is no god, then the sciences have an indefinite role in exploring the farthest reaches of understanding, and therefore have an effectively infinite utility proportional to our understanding.

- If there is a god, then the sciences can only exist as far as we can tangibly know things, which creates a hard limit based on our present technology.

For it to qualify as legitimate science, it must be rigorous, reproducible, and open.

Further reading:

Physical: Particles

The universe is made of atoms, which consist of:

- A nucleon made of protons and (typically) neutrons

- Electrons orbiting erratically around the nucleon

Each atom has an atomic weight, which is mostly made of the protons and neutrons (neutrons are a little heavier), since electrons are comparatively smaller.

Beyond these physical properties, atoms also contain electromagnetic energy.

- Every proton carries +1 e and every electron carries -1 e. Naturally, if an atom has an uneven ratio of protons and electrons, it’ll be positively or negatively charged, and is called an ion.

- This electrical distinction also possesses magnetic forces, demarcated as positive and negative polarity. This creates a type of field around the atom, which can merge with other atoms. That can create eddy currents with nearby magnetic atoms, even if those atoms aren’t necessarily magnetic.

The proton itself is vastly complicated, and science simply doesn’t know the answer. Protons are made of various kinds of quarks:

- The first model is the Gell-Mann and Zweig one, where there are 2 “up” quarks with +2/3 e and a “down” quark with -1/3 e, but it fails to account for the fact that the quarks are constantly spinning and that those 3 quarks are way less mass than the original measurement.

- Once they were able to use a faster particle accelerator, the next model assumed a “strong force” that used charm quarks, which were roped together by gluons, with each quark and gluon having 3 possible charges that all added up together, a bit like how 3 colors combine to create the color white. The theory is that the proton picks up momentary spikes of energy to create a quark and antiquark before disappearing, and the proton is an endless churn of them that creates a “cloud” that looks like a solid object. This model, however, doesn’t explain the 3-quark model at lower speeds.

- Another more recent theory assumes the charm quarks hold the up and down quarks inside them like boxes without extra energy applied, then extra energy makes new charm quarks and antiquarks emerge, and the up and down quarks move out separately from all the quarks. They still have no idea for sure.

Each atom can hold heat energy, which can be measured by how much the atoms vibrate. The more they vibrate, the less they hold together:

- Solids vibrate very little, so they maintain a set structure.

- Liquids vibrate enough to break their structure, but not enough to push away from each other.

- Gases vibrate so hard that they’ll push away from each other if left unattended.

- Plasma vibrates so hard that the atom doesn’t really stay together, and typically only naturally occurs in stars.

Heat transfers through 3 major methods:

- Conduction — a fast-moving hot particle collides with a slower-moving cold particle, and heat transfers on contact.

- Convection — in a fluid (e.g., air, water) heat flows upward through it and churns the cooler fluid downward, which can work as a cycle.

- Radiation — heat can travel over electromagnetic waves (e.g., a star’s light energy).

All atoms exert an incredibly small attractive force toward each other, called “gravity”. This is usually irrelevant for the sake of measuring anything, unless it’s dealing with massive objects (like stars). However, a large enough object will pull on things to tweak that smaller object’s existing motion to make the smaller object travel in an elliptical “orbit” around the larger one. When smaller things are very close to larger things (e.g., standing on a planet), the gravity makes things go downward very fast.

Inside an atom, the state of its electrons typically changes more than its nucleon. It’s pretty common for atoms to gain or lose electrons.

When released, electromagnetic energy radiates outward as measurable photon waves. These waves have vast ranges with wavelengths from 1 picometer (0.0000000001 centimeter) as gamma rays up to 100 megameter (1,000,000 meters) as radio waves. Visible light are the photons between 380 and 750 nanometers (0.000038-0.000075 centimeters).

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Where did the matter in the universe first come from?

- How long has the universe been around?

- Below the subatomic, what are atoms and the universe made from? Dark matter? Dark energy?

- Does a creator of the universe exist?

- Why is ice, as a jagged crystal, slippery?

Physics: Waves & Forces

Atoms interact with other atoms by various forces:

- Inertia is the tendency for a force to stay in motion. There is no centrifugal force from rotation, but there is centripetal force.

- Gravity is an absurdly weak force that draws upon all other atoms.

- Friction is the tendency for atoms to slow down other atoms, often assisted by gravitational pull.

There’s a lot of energy stored in atoms. By separating them (fission) or joining them together (fusion), they will often release this energy. People have already found ways to split atoms quickly (nuclear detonation) and slowly (nuclear power plant).

These atoms can bond together with other atoms (often via opposite ions), and that’s what creates molecules, which then moves into the realm of chemistry.

Photon waves are complicated because they’re both particles and waves, depending on how you measure them. This is the domain of quantum physics, and has very complicated metaphysical implications because the physical properties of particles are defined by whether we observe them or not.

Sound is a wave made from the vibration of molecules that ripple shockwaves across neighboring molecules. For this reason, sound travels fastest and farthest in dense liquid (e.g., water).

Wave effects, both with sound and with light, happen relative to the location of the thing that causes the wave. For this reason, an object moving fast enough toward or away from an observer will appear/sound different for the observer:

- Red shifts (like the longer light wavelength red) come from the distance increasing (such as a car driving away quickly)

- Blue shifts (like the shorter light wavelength blue) come from the distance decreasing (such as a car driving toward someone)

- The best example comes from observing a train honking its horn as it speeds past. First, the train sounds more high-pitched than if it were standing still, then shifts rapidly downward to a much lower pitch as it drives by.

- This red shift/blue shift also blends in with spacetime (proven partially by GPS calculations), so a person traveling near the speed of light will age slower than someone who stays still.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Why does time only move forward? Is time travel possible?

- Is light a wave or a particle? If it’s both, when does it change?

- What causes gravity?

- How does a bicycle stay up while in motion?

Physical: Chemistry

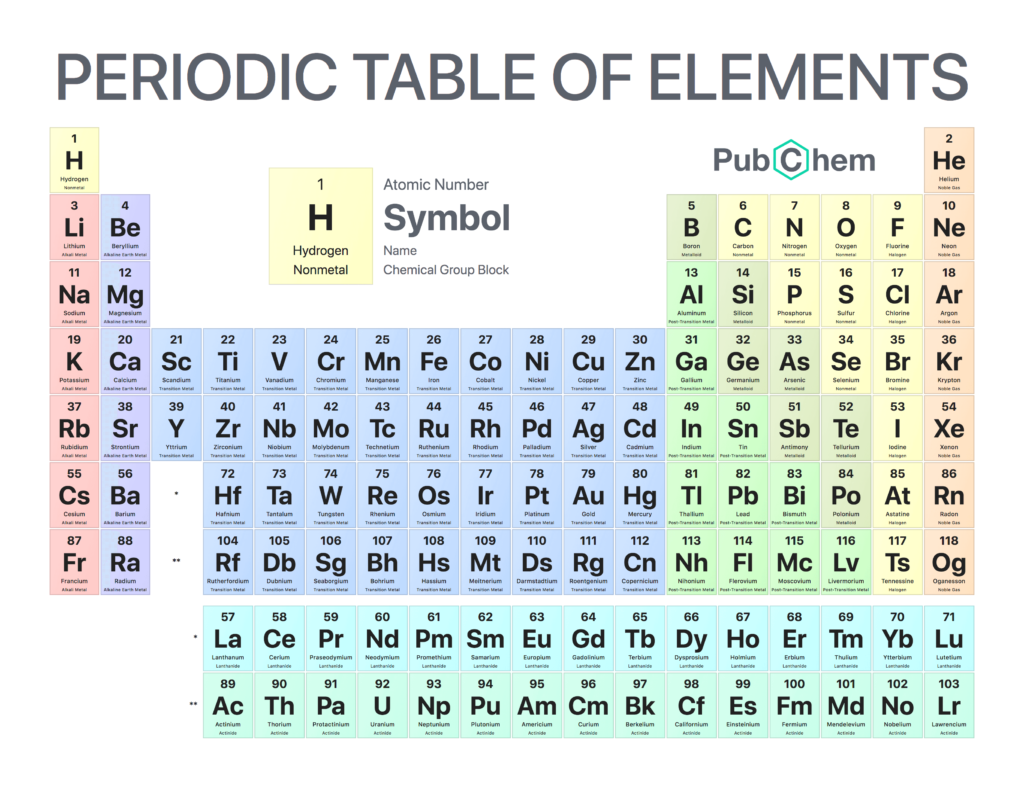

Each atom can be measured on a table, called the Periodic Table of Elements.

Electrons exist in certain layered orbits. The first 2 exist in a “shell”, then the next 8, then the next 18, then 8. The outer shell’s electrons are called valence electrons. Generally, some atoms (like copper, silver, and gold) transmit electrons better because of their relative valence electrons.

Because of valence electrons, certain patterns arise as atoms increase in atomic weight:

- Alkali metals (Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, cesium, francium) – Group 1

- They react very violently with water and create a strong base (alkali).

- Alkali earth metals (beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium, radium) – Group 2

- Like alkali metals, they react violently with water.

- They can withstand heat, and exist naturally within the Earth’s crust.

- Transition and inner transition metals group (Atomic numbers 21-30, 39-48, 57-80, 89-112) – Groups 3-12

- They’re called “transition” elements because they appear to transition from metallic (electrically positive) to non-metallic (electrically negative) as you move rightward.

- Inner transition metals are broadly classified as Group 3 (3rd column) based on how they behave, so they all fit inside that group. They’re also called “rare earth metals”, and are extremely useful in making batteries.

- It’s also worth noting that Group 3 (atomic numbers 57-71 and 89-103) are separated visually at the bottom, simply to save space and make it more aesthetically pleasing when printing it out on a standard sheet of paper.

- Boron/icosagen group (boron, aluminum, gallium, indium, thallium, nihonium) – Group 13

- Carbon group (carbon, silicon, germanium, tin, lead, flerovium) – Group 14

- Tends to be very stable relative to the other elements.

- Nitrogen/pnictogen group (nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, bismuth, moscovium) – Group 15

- Oxygen/chalcogen group (oxygen, sulfur, selenium, tellurium, polonium, livermorium) – Group 16

- Lower-rank chalcogens are often critical to maintain life, but higher-rank chalcogens are often toxic

- Halogen group (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, astatine, tennessine) – Group 17

- When halogens react with metals, they tend to create salts (halogen literally means “salt maker”)

- The specific way they interact with other elements makes chlorine, bromine, and iodine excellent disinfectants.

- Noble gases/aerogens group (helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon, radon, oganesson) – Group 18

- Because their valence electron shells are full, they tend to be very stable.

- Some elements (such as boron), are metalloids because they show properties of metals and non-metals at the same time.

Some atoms have too many or too few neutrons, even though they have the same number of protons and behave the same. These are called isotopes and are represented as a number afterward (e.g., a common uranium isotope is U-238 instead of having 237 neutrons). Their atomic mass is offset by the differing neutrons, and can be calculated proportionally to the composition of variously sized isotopes in a sample. An element’s molecular ratio of its isotopes is easy to detect by observing how they respond to various wavelengths of light (also known as “spectroscopy”).

The higher up the periodic table, the more complex the atom gets, and it generally becomes more unstable. Most of the highest atomic weight elements are either theoretical or were man-made for a fraction of a second before they disintegrated. New technology is constantly making new particles, just to see if it’s possible.

By combining atoms together, they can form bonds that create molecules. These molecules can often be more stable (or unstable) than their individual elements. Table salt, for example, is unbelievably stable, but is made of two highly unstable elements (sodium and chlorine).

When molecules interact, they’re creating a reaction. That reaction will persist until nearly all the molecules have resolved their chemical differences. Other molecules, called catalysts, can interact with that mixture to speed up or slow down that process.

A mixture of different types of molecules together is a solution. In that sense, a Coca-Cola and a hamburger are both solutions. These chemicals tend to interact with each other in different ways, and this implements in various ways that range from cleaning to cooking.

Water is a frequent molecule because of electron bonds. Essentially, oxygen (which has 4 electrons when not ionized) easily pairs with hydrogen ions (which use 1 electron when not ionized). Thus, unionized water is effectively 6 protons and 4 electrons, with the means to be easily ionized by picking up more electrons.

Because of water’s ubiquity, hydrogen ions are frequently part of chemical reactions. The letter p in scientific calculations represents “-log10”, so pH is an inverse measurement of how many hydrogen ions can get released from a chemical. Thus, a weak acid (like black coffee) will release some hydrogen ions, while a strong base (like chlorine bleach) won’t release any. The difference in the releasing of hydrogen ions makes a huge difference in how much the chemicals react with one another.

Physical: Earth Science

We don’t know exactly how this planet was formed. This is hotly contested based on philosophical cosmological beliefs:

- Astronomers say gravity drew the elements from various stars, which clumped together over a very long time until it eventually became what we recognize now.

- Religious people say God formed the Earth as a finished product.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How much can we damage the ecosystem before it stops self-healing?

Geology (Land Science)

Inside the earth, there are multiple layers from all the pressure (which generates heat):

- The crust only goes down for 5–12 kilometers, and is the only thing we’ve ever drilled into.

- The mantle is about 3,000 kilometers thick and made of semi-solid rock. The pressure makes it circulate slowly, and there are a few dozen sections of crust that extend into the mantle as “plates” that move around.

- The outer core is about 3,000-5,000 kilometers thick and made of churning liquid rock, which probably churns from radioactive decay of uranium and thorium and somehow generates the earth’s magnetic field.

- The inner core is 1,220 kilometers thick and might be made of solid iron. There might be an innerer core as well.

Underneath the earth, there are many plates made of that shift. This can create earthquakes, but also can move continents.

The highest naturally occurring element is uranium, and most natural radioactive elements are deep underground. The further down, the hotter it gets. Digging past the crust will quickly yield the mantle, then the core, which is so hot that everything is a liquid.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How could we put carbon back in the earth?

- Why do rocks sail across the desert floor?

Oceanography (Ocean Science)

The earth is ~70% covered in water, with the oceans having vast unexplored territories. The deepest place, the Mariana Trench, is over 10,000 meters below sea level!

Generally, scientists as a whole aren’t often as interested in oceanography compared to the other sciences, for several reasons:

- Even though there are plenty of sunken ships and fun deep-sea life in it, the oceans as an unexplored territory don’t nearly capture the imagination as much as space exploration (i.e., possible life on other planets is often more interesting than life in high-pressure underwater environments).

- The biodiversity of the oceans is rather samey compared to the earth’s land, so it only has ~15% of the species on earth.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How long are any of the coastlines?

- What’s at the bottom of the deepest parts of the ocean?

Meteorology (Weather Science)

The atmosphere around the earth, known as air, is ~78% nitrogen, ~20% oxygen, and a cocktail of other elements. It’s very effective at sustaining life.

Hot air is higher pressure, and the fluid dynamics mean it moves to lower-pressure areas, which creates wind. Clouds are pushed around by wind, and accumulated clouds can create storms.

Clouds float because the water and ice particles are too small to be affected by gravity, and they usually form from the sun’s heat evaporating the tops of bodies of water. Every cloud is simply like fog, but higher up in the atmosphere. The shapes of clouds come from how the wind affects it and how dense the fog is.

Rain is when a cloud has accumulated too much water. About 60% of the water in a cloud falls within 1–2 days, and most water on the ground re-evaporates to become rain within 12 days.

Hail is rain that froze from winds lifting it into clouds over and over.

Lightning is caused by hail rubbing together in clouds to create ionized atoms. They become so ionized that electrons will travel the path of least resistance through the air. Lightning from the top of a cloud is positively charged (where electrons move to the cloud), while the bottom is negative (where electrons move from the cloud).

Physical: Astronomy (Space Science)

We don’t exactly know how stars are formed. This is contested based on philosophical cosmological beliefs:

- Mathematicians say atoms erupted out of a singular point in space very rapidly, then slowed down and drew together to form stars.

- Religious people say God formed the universe with the stars fixed in a starting location already.

Stars fuse elements together to create light. The highest element ever recorded from a star is iron because by the time it reaches iron the atoms are so tightly bound that there’s not enough room to fuse any further.

When a star doesn’t have enough energy to keep fusing, it collapses. Depending on its size, it can become a red dwarf, a white dwarf, have a supernova (i.e., explode), or become a black hole.

Black holes are extremely dense objects. They’re so dense, in fact, that even visible light can’t escape it. For that reason, the only way to measure black holes is to track the stretched-out photon waves that became x-rays.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- What’s at the bottom of a black hole?

Life: Biology

Every living being has a few universal characteristics:

- Sustained by consuming a substance that is then metabolized into energy (that energy measured in calories).

- Consumes some type of gas that transfers carbon into or out of the organism.

- A means to make some form of decision, even if it’s a rudimentary impulse.

- Some form of “skin” that establishes a clear boundary against the surrounding environment.

In many ways, the structures that form life are akin to remarkably well-designed technology, with many built-in redundancies and fail-safes.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How did life begin?

Life: Biochemistry

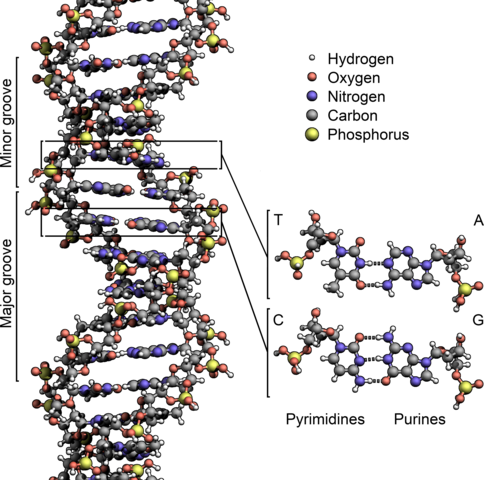

Life as we understand it uses DNA, which stands for deoxyribonucleic acid, with molecules arranged in a double-helix structure.

DNA is made of a very specific chain of nucleotide base pairings of A-T (adenine-thymine) and C-G (cytosine-guanine). This creates 4 permutations (each of the two flipped back-and-forth), which makes all life effectively a type of computer.

Each DNA strand is arranged into extremely long strands, with 2 strands in a chromosome. Different forms of life have different numbers of chromosomes, with humans having 23 and all life ranging from 1 to 1200 chromosomes, though it’s not apparent by looking at any living creature how many chromosomes it has. The very last chromosome determines gender differences with X and Y chromosomes, and the rest are called autosomes.

- Any location in a gene sequence is called a locus, and variations of those sequences are called alleles. A group of alleles that inherits from a single parent are called haplogroups, which pair together to form chromosomes.

- The very last chromosome of a male is XY and a female’s is XX. When they mate, they give one chromosome each, meaning that it can be 4 possible combinations with an approximate 50% chance of a gender (Xm+Xf1, Xm+Xf2, Ym+Xf1, Ym+Xf2).

- Autosome traits can be dominant or recessive. Some traits (e.g., red hair, sickle cell anemia) require both parents to contribute their recessive genes. Others (e.g., blue-yellow color blindness, Marfan syndrome) only require 1 parent to send their autosome.

- On rare occasion, offspring can possess two sets of genes (chimerism) and a DNA test that only tests one set won’t pick up direct ancestry from the other (especially with bone marrow transplants). This can happen with organ transplants or abnormal events during birth.

DNA has a vastly specific programming. All life shares the same ~60% DNA, with the differences arising from the remaining differences.

Beyond DNA, there are several other components necessary for life:

- Proteins, which are chains of amino acids (amino and carboxylate) that form a fixed structure.

- Carbohydrates, which are easily-broken-down chains of carbon/hydrogen/oxygen chemicals.

- Lipids, which include fats, oils, and hormones that aren’t soluble in water.

We don’t exactly know how life formed in the first place. This is contested based on philosophical cosmological beliefs:

- Biologists say a series of electrochemical reactions formed the existing protein strands that eventually coalesced into what we know as organic life.

- Religious people say God created organic life fully formed already.

Depending on the belief system, the taxonomy is dramatically different:

- Kingdom – Plants, Animals, Protists, Fungi, Monids

- Phylum – a further subdivision into various traits of each (e.g., arthropods)

- Class – further subdivisions into various broad classifications (e.g., amphibians, reptiles)

- Order – further subdivisions (e.g., primates, rodents)

- Family – clearly demarcated subdivisions that everyone agrees on irrespective of cosmological values

- Genus – further classifications that delineate nuances in families

- Species – the final division that demarcates idiosyncrasies between various organisms

While we’ve sequenced the genome to measure where various traits are located, we haven’t completely sequenced it. Instead, as of 2023, we still use the “shotgun method”, which involves grabbing chunks of gene sequences and using statistics to model the rest.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Will we ever fully cure cancer?

- Why do we have blood types?

- How long can we possibly live?

- What do probiotics do?

Microbiology

Cells are the simplest expression of life, and they all have at least most of the same characteristics:

- A nucleus that contains the DNA of the cell.

- Ribosomes that read the nucleus’ DNA and make corresponding copies of that DNA with RNA (with uracil instead of thymine).

- A semi-porous cell membrane with a lipid bilayer that lets stuff in and out of the cell, often shaped in a way to only let certain chemicals in that it may need.

- Cytoplasm, a fluid made of mostly water that fills up cells.

- Mitochondria that use ATP (adenosine triphosphate) or photosynthesis to give energy to the rest of the cell.

- Lysosomes that break down unwanted things in the cell.

- Endoplasmic reticulum, a framework for processing chemicals, which are either “rough” (with ribosomes on it) or “smooth” (for processing hormones and lipids).

- Golgi apparatus, an “outbox” where the endoplasmic reticulum sends everything into the cell wall or out of the cell.

Further, plants have a few components of their own:

- A cell wall with a cellulose layer that gives extra structure to the organism.

- Chloroplasts that help with photosynthesis (using photon energy for metabolism).

- Vacuole that serves as a storage space for the cell (often filled with mostly water).

On the cellular level, reproducing life asexually (mitosis) is a relatively straightforward process:

- The nucleus sends “messenger RNA” (mRNA) to the ribosome.

- The ribosome uses stuff like “transfer RNA” (tRNA) and “ribosomal RNA” (rRNA) to gather proteins to build more DNA.

- Once the second DNA is built, the cell lines up everything together, then creates a new cell membrane to split it cleanly in half.

By contrast, more complex life reproduces sexually (meiosis) with another relatively straightforward process:

- A male sperm (which has all the DNA of the male) penetrates the cell membrane of a female egg (which has all the DNA of the female).

- The egg splits and lines up the chromosomes of each, then takes half of them.

- That one half-of-each DNA hybrid is the basis of the new cells, which rapidly keep splitting according to their instructions, a bit like mitosis.

It’s worth noting that sexual reproduction requires similar-enough animals. While cross-species mating isn’t uncommon and cross-genus mating is sometimes possible, cross-family mating isn’t.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Can, and how can we beat bacteria?

- How do mitochondria work?

Botany

Moving up from simple plant life, most plants have a distinct fractal-like pattern and tend to use photosynthesis. Plants tend to breathe carbon dioxide (CO2), then strip the carbon and emit oxygen as a waste product (O2).

Plants draw nutrients from the soil they live in, then combine it with CO2 from the air and sunlight to grow. Once they’ve grown enough, and the climate conditions are right, they will produce fruit with seeds in it to nourish the future of its kind.

Plants communicate frequently. They send signals through their roots, as well as scents to attract animals and warn other plants, and plants send ultrasonic sound waves when they’re hurt.

Zoology

Beyond cellular life, animals have a more complex existence than plants. They tend to breathe oxygen (O2), then add carbon from their metabolism and emit carbon dioxide (CO2).

A unique quality of fauna is a central control system via a brain. That brain runs on hormone signals that run small bits of electricity through many neuron pathways. Each neuron has a big block called a soma (gray matter), with an extension called an axon that’s coated in a protective myelin (white matter). The neurons connect via continued exposure to build an automated system of habits for responding and interacting with the world.

Except for bugs and some underwater creatures, animals have their skeletons on the inside, with muscles operating them.

As a whole, a brain consists of several inter-related parts:

- A brain stem connected to the spinal cord that manages very basic motor skills and sensations.

- A cerebrum that makes up most of the volume of the brain that controls most activities:

- The frontal lobe is the largest, and regulates personality, decisions, and movement.

- The parietal lobe helps identify objects and make relationships between things.

- The occipital lobe is at the back, and regulates vision.

- The temporal lobe is on both sides of the brain at the bottom, and regulates how we perceive time and make stories, which translates to short-term memory, speech, musical rhythm, and some aspects of smell.

- A cerebellum that manages higher thought such as reasoning and imagination.

- The brain is split into two hemispheres, with the left side generally managing more logic and the right side more emotions. Each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body.

- Within this framework, there are many deeper structures inside the brain that perform very specific things:

- The pituitary gland is a pea-sized chunk right behind the bridge of the nose and regulates the function of other glands in the body.

- The hypothalamus is right above the pituitary gland and sends chemical messages to regulate body temperature, synchronize sleep patterns, control hunger and thirst, and influence parts of memory and emotion.

- The pineal gland is very deep in the brain and manages sleep cycles with the hormone melatonin.

- Also, the limbic system is heavily connected to the brain stem, but extends outward into the cerebrum:

- The brain emits various types of waves:

- Delta waves are when a body is in a state of deep sleep.

- Alpha waves express when the body is in a state of rest.

- Beta waves express when the body is alert and engaged.

- Theta waves are present when someone is daydreaming or in a flow of ideas, and often help remember things connected to space.

Animals require food, which can come from several sources:

- Herbivores eat plants, often existing as prey to other animals.

- Carnivores eat other animals, often as predators.

- Omnivores eat both plants and animals, and may be predators or prey depending on the situation.

- One newly discovered microorganism is a virovore, which eats viruses.

One unique trait of animals is the means of communication via vocal cords. The concept is relatively simple: constrain the flow of air in such a way that sound is produced. This implementation varies wildly across animals, but the abstraction stays the same. Humans, among others, have a unique addition to that with tongues that give very precise control over those sounds, and that’s how we orchestrate language.

Further reading:

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- Why do we need sleep?

- Why do we dream?

- Why do we yawn?

- Why do we have fingerprints?

- Why do giraffes have long necks?

- Why do cats purr?

- Approximately how many species of animals exist?

Ornithology

Birds are typically defined by egg-laying, moderate nurture of their young, and feathers directly inserted into the skin.

A bird’s feathers are typically hollow, which gives the lightweight composition necessary to fly.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How do birds migrate to the same area every year?

Entomology

By far, bugs represent the largest zoological population: most multicellular life on this planet are bugs.

Most of them have a common anatomy:

- Bugs have exoskeletons, with their muscles underneath.

- Antennae/feelers that detect the world around them.

- A head section that represents the same as in mammals.

- Typically, a thorax segment with most of the internal organs.

- An abdomen segment that either contains a specific-purpose organ (e.g., venom sac) or most internal organs (if it doesn’t have a thorax).

- Typically, 3 pairs of symmetrical segmented legs, but that number can sometimes be 4 (e.g., spiders) or more (e.g., centipedes, millipedes).

- Depending on the species, wings that empower it to fly. Often, there will be a wing pad on top of it to protect the wings from damage.

Flying bugs navigate around light sources at night because of a navigational error. When the sun is out, they can orient themselves to the light and fly straight, but they’re always angled to fly relative to the light source at night as well, meaning they’ll keep autocorrecting and be caught in a loop.

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- How do monarch butterflies know how to migrate?

Life: Ecology

The combination of weather and geological formations create several major types of biomes across the earth:

- Aquatic biomes are underwater, with the dominant life being fish.

- Grasslands are warm and dry, with mostly smaller plants like grass.

- Forests have more moisture to support densely packed trees.

- Deserts are extremely dry (<20 inches of rain per year) but aren’t necessarily hot.

- Tundra are freezing (-34° to -12° C), and are essentially an icy desert.

Most life on earth is underwater, and most air-breathing life are bugs.

Nothing is technically ever wasted by living beings. Every waste product of a living being is sustenance for another:

- Dung beetles and flies eat mammal excrement.

- Oxygen is toxic to flora and critical for fauna, and the reverse for carbon dioxide.

- Most odors we find unpleasant are because we’ve incubated a microbiome.

The scarcity of food creates a hard limit on how much and how varied life can thrive, and builds a type of food chain. A good rule of thumb is that, barring plant life, every organism requires 1,000 times its biomass to survive. Thus, a 5-kilogram herbivore requires 5,000 kilograms of plant matter and a 5-kilogram carnivore requires 5,000 kilograms of herbivore (i.e., 5,000,000 kilograms of plant matter). This is a giant reason why most predators don’t primarily feed on other predators.

Generally, an ecosystem thrives when there’s plenty of water and plenty of sunlight. This gives tons of plant life, which allows more animals to survive, meaning more speciation.

Sadly, climate science has been hijacked for political reasons, often pointing the blame for biome degradation on carbon. Increased carbon output, however, would trigger the negative feedback loop of increased plant life, thus preparing for more animals to offset the situation.

Over time, evolutionary adaptations change the epigenetics of organisms, but its scope and timing of the raw data leans heavily into the phenomenology of the data-viewer’s perspective of the unknown:

- Atheist biologists believe all speciation came from a common ancestor, meaning it took millions of years and a few decades of reckless behavior by mankind could upset the delicate balance of existence we live in. Their timing for the conditions frequently moves around as they uncover new data.

- Deist apologists have a wider range of beliefs, often believing that epigenetics creates speciation over a comparably smaller period of time, meaning adaptations can (generally) keep pace with mankind’s adverse decisions.

New species are forming and dying all the time, and it’s very difficult to keep up with all of them. Even with our technology, we can’t entirely track all the flora (with many of them having healing properties), or all the derivatives of fauna. We’re either ill-suited for the task, or the adaptations happen within generations (and not necessarily millions of years).

Social Sciences

As stated above, all the social sciences are a “soft science” because the human mind is vastly complicated, and examining it is inherently recursive. Most of the solid scientific principles float back to neurology, which is itself more a division of biochemistry.

However, the domain of psychology may be the “hardest” science in this field because it observes human behavior and bias mostly in a vacuum. It only gathers a small portion of the picture, though, since we are very social creatures.

To make matters even more complicated, some “fixed” things like DNA are influenced by psychological states. Parents’ trauma, for example, can pass on through genetics, further complicating an already-hazy “nature vs. nurture” debate within psychology.

There are many social sciences, and they all have a limited scope of influence:

- Sociology — measuring how groups of people behave

- Cultural anthropology — measuring comparisons of how groups of people behave

- Political science — measuring how to govern large groups of people

- Economics — measuring interactions and activity in large groups

Obvious questions that remain unanswered:

- What is the purpose of living?

- Why does the placebo effect work?

- Why are 9 out of 10 people right-handed?

- Can we make an AI that’ll sustain a believable human-like conversation?

Applied Sciences

All of the above sciences apply to the world around us, and that application naturally merges into the domain of engineering.

The formal sciences work to create:

- Data and information science, which blurs heavily with computer science

- Systems theory, which is essentially the corporate explanation for all the scientific information

Physical and life sciences end up creating, among others:

- Engineering

- Agricultural science

- Almost the entire medical industry

- Health sciences

Social sciences build out, among others:

It’s worth noting that social fashions dramatically sway all scientific values, mostly because very intelligent can often have absolutely no common sense.