Accounting is the language of business.

- Accountants track the numerical history of transactions, then express the most relevant information in reports.

Understanding how accounting works allows you to understand where the transactions flow from.

- Most of the system is automated with spreadsheets or accounting software, so most people only need to maintain conceptual awareness of how it works.

Accounting isn’t strictly a discipline of math.

- Math uses complex calculations, and accounting doesn’t use anything above algebra.

- Accounting, does, however, use large columns of numbers.

- In that sense, accountants create databases more than performing mathematical calculations.

Mindset

Accounting is a distinct trade with a few idiosyncratic details.

These details are not intuitive, but they’re not difficult to explain.

Double Entry

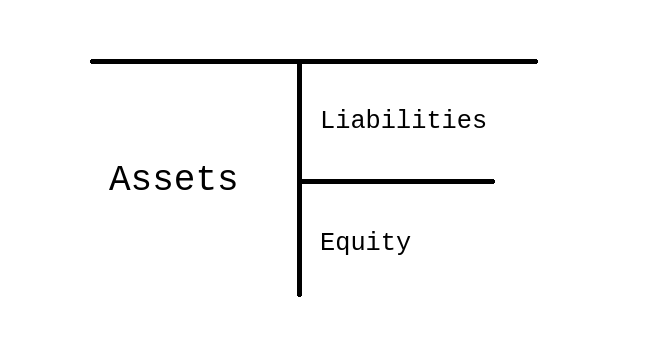

On the back-end, all accounting uses the double-entry accounting system.

- Every account in the account ledger only sits within 3 possible domains (as shown above):

- Assets – things you have

- Liabilities – things you owe

- Equity – things left over as profit/loss (i.e., Assets – Liabilities)

- All transactions have 2 sides to it:

- A debit (“debir” or “Dr”) on the left side.

- A credit (“credir” or “Cr”) on the right side.

- All the debits of a transaction will equal all the credits.

- There is no inherent meaning to debits or credits without the account it’s related to.

- Debits are typically used for assets and expenses, and credits are typically used for liabilities and income, but it reverses when the books are closed and there are counter-balancing accounts to many of them.

- In general, if you have to anchor a concept, think of how the number goes up:

- If it’s assets, debit means up.

- If it’s a liability, credit means up.

- If it’s equity, credit generally means up, but then debit means up when equity zeroes out at the end of the period.

- The debits and credits have meaning relative to their placement in the account ledger:

- Assets – debit means it goes up, credit means it goes down (e.g., a bank’s debit/credit card is relative to them).

- Liabilities – debit means it goes down, credit means it goes up (e.g., getting a new loan will be a new credit).

- Equity – debit goes to Expenses, credit goes to Revenue.

- Every transaction traces movement between the accounts:

- Getting a $1,000 loan – Debit $1,000 to Loan Expense, Credit $1,000 to Outstanding Loans.

- Buying $200 of inventory – Debit $200 to Inventory, Credit $200 from Cash.

- Selling $100 of inventory for $150

- Debit $100 to Cost of Goods Sold, Credit $100 from Inventory.

- Debit $150 to Cash, Credit $150 to Sales Revenue.

- At the end of the period, make closing entries to the Equity accounts to zero them out for a new period:

- Debit all Revenue accounts to make them $0, Credit the same amount to Retained Earnings.

- Credit all Expense accounts to make them $0, Debit the same amount to Retained Earnings.

The essence of double entry is that absolutely everything must be rigorously organized and micromanaged.

- Since all debit and credit transactions add up to zero, it’s patently obvious at the transaction level when something is wrong.

- Every single thing’s philosophical status (i.e., its purpose or essence) is represented by an account.

- Every time there’s a change to that thing, it’s affecting something else (i.e., a different account) and must be recorded as well.

- If it’s trading one “thing” for another “thing” (e.g., buying inventory), it’s asset-with-asset.

- If it’s trading a “thing” for a future promise (e.g., getting a loan) or fulfilling that promise, it’s asset-with-liability.

- If it’s an account outside the organization (e.g., a bank account) it’s reproduced precisely the same as an asset or liability.

- If it’s strictly conceptual (e.g., a donation or making money), it’s an equity account (income if it makes more money and expense if it loses money).

Accounting Philosophy

Accountants live and die by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

- Any accountant who doesn’t abide by GAAP is violating the rules that govern any accounting, and is setting up their organization and themselves for a bad time in the future.

- GAAP has 4 assumptions, 4 principles, and 4 constraints.

Assumption 1 – Accounting Entity

- The organization is logically separate from its owners and other organizations.

- As much as possible, revenue and expenses for the entity aren’t affiliated with personal expenses.

- Without it, the boundaries between entities gets complicated or nonexistent and opens everything up to abuse and fraud.

Assumption 2 – Going Concern/Continuity

- Except for a 100% liquidation, the organization will keep operating indefinitely into the unforeseeable future.

- This assumption validates several methods:

- Whether an asset is fixed vs. current

- Short-term vs. long-term liabilities

- Capital and revenue expenditures

- The changes in value of an asset (Capitalization, Depreciation, and Amortization)

- Without it, there will be no means of projecting what to do in the farther future.

Assumption 3 – Monetary Unit Principle

- The unit of record must be a stable currency.

- The FASB accepts the nominal value of the US Dollar, unadjusted for inflation.

- That currency is as fixed as possible to accurately reflect value compared to everything else.

- In other words, the USD is the standard of currency because everyone uses it as the standard of currency.

- Barring a major upset in the world economic system (this was written in 2023) even other currencies are pegged to the dollar.

- Without it, there’s no clear, measurable certainty on the value of anything relative to other items or periods.

Assumption 4 – Time-Period Principle

- An entity’s economic actions are divided evenly into artificial, fixed, equally sized periods.

- As much as possible, attach revenue and expenses together in the same periods using cut-off procedures.

- The time divisions are typically monthly, quarterly or yearly but can go down to weekly, daily or hourly if needed.

- Without it, there’s no clear way to define how an organization performed during a period of time relative to other periods.

Principle 1 – Historical Cost Principle

- The costs of most Assets and Liabilities must be based on how much they paid, and not fair market value.

- While it conflicts with marketing (and investors, to an extent), it avoids subjective or biased values based on the market.

- This principle doesn’t always apply: most debts and securities report at market values.

- Without it, the value of things can be over-stated, meaning extreme dissatisfaction and potential complications later on when the value is more accurately determined (instead of simply dissatisfaction right now).

Principle 2 – Revenue Recognition Principle

- Organizations must either record when they receive revenue (Cash Basis) or when they earn it (Accrual Basis).

- Most organizations, for various legal and contractual reasons, can’t use a Cash Basis.

- Without this distinction, the cash flow becomes hard to clearly track.

Principle 3 – Matching Principle

- As long as it’s reasonable, expenses must match with revenues.

- Expenses are recognized when they contribute to revenue, not when they’ve incurred.

- Expenses can be charged to the current period, but only if they can’t trace directly to revenue.

- This principle allows more accurate analysis of profitability and performance (e.g., Depreciation, Cost of Goods Sold).

- Without it, it’s difficult to determine and measure the relationship between various business activities.

Principle 4 – Full Disclosure Principle

- Preparing and using information costs money, so analyzing the tradeoffs determines which information should be disclosed.

- Accountants can store their information in the main body of financial statements, in the notes, or as supplementary information.

- The disclosed information should provide enough knowledge for all organizational decisions, but shouldn’t become unreasonably expensive.

- Without it, accountants would endlessly peruse the record keeping and drive a company out of business.

Constraint 1 – Objectivity Principle

- Financial statements that accountants provide to the organization must use objective evidence.

- A massive aspect of accounting involves documenting and recording evidence of already-existing information.

- Without it, the organization wouldn’t be durable to the criticism and audits of other entities.

Constraint 2 – Materiality Principle

- An item should only be reported if it might affect a reasonable individual’s decision.

- Without it, accountants would gather endless useless information.

Constraint 3 – Consistency Principle

- From period to period, an organization must use the same accounting principles and methods.

- Like the Time Period Principle, there’s no clear way to define without it how an organization performed during a period of time relative to other periods.

Constraint 4 – Conservatism Principle

- When accountants must decide, they should pick the solution that least overstates assets and income.

- Like the Historical Cost Principle, the value of over-stating things means extreme dissatisfaction and potential complications later on when the value is more accurately determined (rather than simply dissatisfaction right now).

The Accounting Cycle

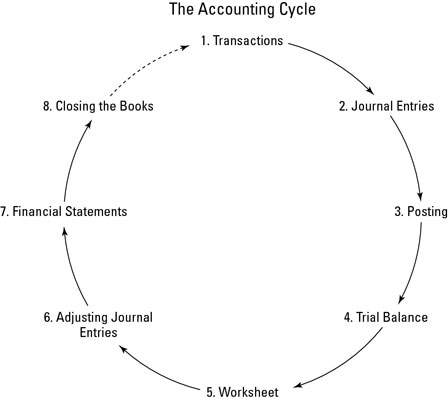

The routine of accounting breaks each period into an 8-step accounting cycle:

- Identify transactions – this can require a human accountant, but can be largely automated.

- It’s simply a matter of detecting movement of anything with value:

- Selling or returning a product.

- Purchasing supplies.

- Exchanging assets.

- Borrowing or paying off a debt.

- Depositing from or paying the organization’s owners.

- Losses from natural disasters or theft, or collecting an insurance payment.

- Cash basis looks only at events that have happened, while Accrual basis looks at promises of events happening as well.

- It’s simply a matter of detecting movement of anything with value:

- Journal entries – use language to articulate chronologically what happened.

- The first accounting documentation is in the journal.

- Each journal entry always affects at least 2 accounts (as shown above).

- Posting – record the same information from the journals to the General Ledger.

- It’s effectively the same information, but classified by account and without the story of what happened.

- Trial balance – calculate the total balances at the end of the period.

- This is a redundant step that ensures the debits and credits are clearly balanced before moving forward.

- Worksheet – for any discrepancies in the trial balance, make corrections (adjustments) on a worksheet.

- This step isn’t necessary in a small cash-basis organization, but things rarely stay simple in a large organization.

- Adjustments also account for one-time payments that affect multiple periods:

- Depreciation divides out the deterioration of multi-year (long-term) assets.

- One-time payments for longer-term assets (e.g., insurance) are divided out to accurately match expenses with revenues.

- At the end, take another trial balance to ensure the adjustments balance out the accounts.

- Adjusting journal entries – post any worksheet adjustments as journal entries to the affected accounts.

- This step is the cumulative effort of the worksheet stage.

- Financial statements – produce all the financial statements (more detail below).

- Close the books – zero out the revenue and expense accounts (as shown above).

- This phase is also usually where stock dividends and other adjusting equity accounts are managed (more detail below).

Now that computers can error-check everything and fix errors automatically, the cycle isn’t completely critical, but accountants like its redundancy because it gives more possibilities of catching errors.

For the sake of convenience, accountants organize the accounts by numbering them with an approximate convention:

- 1000-1999 Asset accounts

- 2000-2999 Liability accounts

- 3000-3999 Equity accounts

- 4000-4999 Revenue accounts

- 5000-5999 Cost of Goods Sold accounts

- 6000-6999 Expense accounts

- 7000-7999 Other Revenue accounts (e.g., interest income)

- 8000-8999 Other Expense accounts (e.g., income taxes)

Reporting

Four major reports are very commonplace.

- These “financials” are top-level descriptions of the organization.

- However, other reports can drill into as much detail as the interested parties care to go.

The Income Statement shows financial performance over time.

- They’re the most important because they most significantly reflect performance.

- At the beginning of the period, the Income Statement balance is zero.

- Every cycle, the books close and set the balance back to zero.

- Revenue – Expenses = Income (i.e., Profit or Loss)

- Broadly, Expenses are grouped into two categories:

- Operating Revenue & Expenses, which are directly associated with the organization’s operations.

- Non-Operating Revenue & Expenses, which is everything else not directly related to the organization’s operations.

The Balance Sheet shows a financial position on a specific date.

- It breaks out the above-stated Asset, Liability, and Equity accounts for a given date.

- At the end of each year, Net Earnings/Income are added to Retained Earnings on the Balance Sheet.

- It’s the easiest to produce, since it’s basically the General Ledger without all the details.

The Statement of Cash Flows shows how money flows in and out of various activities.

- There are 3 major activity groups:

- Operating activities – keeps the organization going.

- Investing activities – manages assets to keep operating activities going.

- Financing activities – expands and grows the organization through loans, others’ investments, or donations.

- Without computer assistance, Cash Flow Statements are tedious to generate.

The Statement of Changes in Equity shows the changes in equity across a period.

- Equity is the organization’s net worth, not its actual value.

- Statement of Changes in Equity isn’t very useful for internal decisions nearly as much as for investors, so it’s usually not bundled with the other three.

The statements could best be described by comparing the organization to a fruit-bearing tree:

- The Balance Sheet is a slice of the tree’s trunk, which is the foundation of what produces the fruit.

- The Equity/Net Worth/Accumulated Retained Earnings section of the Balance Sheet approximates the value of the organization.

- The Income Statement is the fruit gathered for a window of time.

- Some years are lean with little or no Net Income, and others are strong with plenty of Net Income.

- The Cash Flow Statement shows where the cash traveled in the organization.

- It shows how much of the Income Statement produced a yield (Operating/Investing Activities) and how much the Balance Sheet helped grow the organization (Financing Activities).

Typically, the reports are often bundled together into an Annual Report.

- Beyond the standard reports, they can include forecasts that try to predict future financial periods.

Most managerial accounting involves creating specialized reports to fit the needs of the people who influence a large company.

- To create the reports, most of the data on graphs is smoothed out to show lines that indicate a trend instead of jagged points.

Some financial statements are required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to more clearly clarify equity-based information for owners:

- Proxy Statements help shareholders make informed decisions about matters that will be addressed at a stockholder meeting.

- Prospectus provide details about an investment’s offering (i.e., stocks, bonds, mutual funds) to the public.

- A Confirmation indicates a legally affirmed indication of a completed trade.

Even when a company is liquidated or merged into another company, the financials must still reflect those periods of time and what happened.

Endless Details

Beyond the above, accounting is a world of endless details.

- More than anything else, accounting looks at each small thing from the bottom-up.

- Unless someone is on the autism spectrum, they’re not qualified to work well as an accountant.

This is by no means exhaustive, but is thorough enough to cover important components.

Assets and liabilities can be classified as short-term or long-term.

- Short-term is expected to have use for less than 12 months (e.g., supplies, short-term loan).

- Long-term is expected to last longer than 12 months (e.g., autos, mortgage).

Many accounts are kept at zero (zero-based):

- All equity accounts are zero at the beginning of the period, and must become zero again at the end.

- Beyond the accounts that show on financials, accountants typically create suspense accounts, which are intermediate-stage holding containers for complex accounting procedures.

Throughout the record keeping, accountants often plug small numbers to correct rounding errors.

- While some accountants can become insanely petty over a $0.01 discrepancy, it’s often caused by a typographical error.

Finding errors is a massive part of the labor that goes into accounting:

- Errors of omission mean it wasn’t entered at all.

- Entry reversal swaps a credit entry with a debit.

- Transposition errors swap digits inside numbers (meaning the discrepant amount can be divided by 9).

- Rounding errors adapt the number to an approximate value, and can create a snowball effect later (e.g., 2.9 becomes 3).

- The two-based number system of computers means computer-based accounting is always at risk of rounding errors.

- Errors of commission mean it was entered correctly to the correct account, but the value is wrong (e.g., applied payment to the wrong invoice).

- Error of principle (aka “input error”) means it doesn’t conform to GAAP.

There are some ways to make error-searching easier:

- If the discrepant amount is divisible by 9, two numbers were probably transposed.

- If the discrepant amount is divisible by 2, the erroneous number probably had an extra digit.

- If the discrepant amount is divisible by 10, a decimal may have been misplaced.

- When the error matches a common transaction amount, it may have been entered twice or omitted.

Assets

All assets can be classified as tangible or intangible assets.

- Tangible assets are things you can point at (e.g., an auto or building).

- Intangible assets are conceptual ideas that still have value (e.g., intellectual property, insurance).

They can also be current or non-current.

- Current/convertible assets are used within the next 12 months and can typically be converted to cash easily:

- Cash on hand

- Cash in banks

- Money owed

- Petty cash (an obsolete concept now that bank cards exist)

- Raw materials and stock

- Pre-payments on insurance or rent

- Non-current/fixed assets will severely affect day-to-day operations if converted to cash:

- Land

- Buildings

- Machinery

- Vehicles

- Contingent assets are likely future assets, such as accounts receivable.

- A debt is certain, but collecting a debt isn’t, so contingent assets are more scrutinized than contingent liabilities.

A circulating asset is what most people think of when they imagine “business“:

- Convert cash to goods (e.g., manufacturing materials, inventory).

- Do something with the goods.

- Convert the goods back to cash again, hopefully more than the first time.

The point of sale is the location where a transaction occurs, and accounting treats the exchange as having at least 2 transactions, which often represent informally on a receipt:

- The customer providing payment or promise of payment for the product (debit an asset, credit Sales).

- If applicable, they will have to move the money from the point of sale to another location (debit Bank Account, credit Undeposited Funds).

- The company providing the product from inventory or a service rendered from a worker (debit a liability or Cost of Goods Sold, credit an asset).

- If applicable, sales tax (debit Tax Expense, credit a tax liability).

- If, for some reason the payment doesn’t go through, the vendor may charge a Not Sufficient Funds (NSF) fee for the inconvenience.

Whenever there’s cash on hand, there will be errors.

- If there aren’t any errors at all, it’s likely the workers are being very particular about keeping records because they’re trying to steal from the company.

- The best way to address the problem is to make sure via company policy that the errors are the safest type of error (e.g., collected cash but didn’t record it).

Accounts Receivable (A/R)

While the customer needs grace to work with their finances, managing A/R is absolutely critical to maintain cash flows, and some things are still “receivable” even when the company only uses cash receipts:

- Bills sent for rendered services.

- Outstanding loans which need to be paid by other entities.

- Written arrears for clients/customers to make future payments.

A/R uses some shorthand terms when invoicing for specific, common arrangements:

- Payment in advance – customer must make a deposit or payment before starting work (e.g., 50% payment in advance).

- Due upon receipt – typically, customer must make payment by the following business day after receiving the invoice.

- Pay on delivery – the customer must pay when the product is delivered.

- Net # – various terms that give a set number of days before payment is due (e.g., Net 7 means the buyer has a week to pay it).

- The most common are Net 7, Net 10, Net 30, Net 60, and Net 90

- It’s not uncommon to start with Net 7 for new customers and give Net 90 to loyal, long-time customers.

- X% # Net # – customer receives a percentage discount if the invoice is paid with a certain number of days, or the full amount is due in a longer number of days (e.g., 2% 10 Net 30).

- Line of Credit Pay – customers can pay the invoices over a longer routine period of time, such as monthly or quarterly.

- End of Month (EOM) – due at the end of the month, irrespective of when the invoice was created.

- Cost, Insurance and Flight (CIF) – The seller agrees to pay shipping, insurance and freight charges before the item is delivered.

People sometimes don’t pay their bills, so organizations need a procedure for managing them:

- Before it happens, the contract should clearly indicate late fees and the consequences for what should happen.

- Try to contact them about the unpaid debt.

- Write off the debt as Bad Debt Expense.

- Make a record to prevent them from abuse the situation again.

When there are many entities to manage, a debt-by-debt solution is impractical, so they use an Aging of Receivables to accurately track the likelihood of non-payment:

- Make a chart that breaks apart the late payments into time-based categories.

- e.g., 1–30 days, 31–60 days, 61–90 days, 91+ days

- Assign progressively increasing percentages for each section.

- e.g., 1-30 is 5%, 31-60 is 10%, 61-90 is 15%, 91+ is 20%.

- Keep track of every account within each category.

- During the adjusting phase, use the applicable percentage of each category to create the posted Bad Debt Expense.

Depreciation/Amortization

The value of assets goes down over time, so accountants must clarify that deterioration of value.

- If it’s a fixed asset, it depreciates.

- If it’s an intangible asset, it amortizes.

The value of fixed assets are typically assessed at their replacement cost, minus their scrap value.

While accountants typically only amortize on a straight-line basis (the first example here), they can choose from multiple ways to depreciate a fixed asset.

- Straight-line depreciation – the most common and simplest:

- (Asset Cost – Scrap Value) / Asset’s Useful Life

- The depreciation rate doesn’t change over the life of the asset.

- While it spreads the expense evenly across accounting periods and easy to automate in most software, determining the useful life of the asset takes lots of guessing and a miscalculation could over-value the asset for several years.

- Declining balance depreciation – an accelerated method that depreciates assets more in their earlier years:

- Asset Value x Straight Line Depreciation Percentage

- Double declining balance depreciation – an accelerated method when assets are very productive in their early years:

- Asset Value x Straight Line Depreciation Percentage x 2

- It writes off an asset’s value the quickest, but the calculations are more complex than other methods and typically use a depreciation schedule to only have to calculate it once.

- Sum of the years’ digits depreciation – an alternate accelerated depreciation method:

- (Remaining Asset Life / Sum of the Years’ Digits) x (Asset Cost – Scrap Value)

- The sum of the years’ digits is calculated by adding the digits together (e.g., 5 years is 5+4+3+2+1).

- Not as fast a devaluation as double declining balance, but faster than straight line.

- Gives control over the depreciation expense recorded each month, but also is the most difficult depreciation method to calculate.

- (Remaining Asset Life / Sum of the Years’ Digits) x (Asset Cost – Scrap Value)

- Units of production depreciation – defined by how many of items something can produce:

- (Number of Units Produced / Asset Life in Units) x (Asset Cost – Scrap Value)

- It’s easy to calculate and more accurate than straight-line, but requires keeping an accurate record of the number of items it produces (which will likely vary month-to-month).

While every long-term asset could technically be depreciated, many items are simply easier to expense for tax reasons than bother with depreciating (e.g., brooms, computers, etc.).

Typically, the amortization of a loan is from how the bank sees it, since debt payments are accounts receivable to them.

Inventory Tracking

Accountants can track expenses for inventory in several ways. This reflects as “cost of goods sold”:

- Average Cost Method – Find the average cost of all current inventory (Total Inventory / Number of Items), then make that the value of each inventory item. This one isn’t used much because it requires more calculation.

- First In, First Out (FIFO) – As inventory is depleted, use the earliest inventory’s costs. The IRS likes this one, but many organizations don’t because it typically reduces income (and tax payments) the least.

- Last In, First Out (LIFO) – As inventory is depleted, use the latest inventory’s costs. This can easily lower profit, which can reduce tax payment.

- Highest In, First Out (HIFO) – As inventory is depleted, select the most expensive inventory’s costs. This only applies to very specific circumstances, but is the best way to reduce tax payment if it’s permissible in tax law.

Manufacturing plants have extra categories of each inventory item:

- Raw Materials – The incoming items as they’re shipped into the factory.

- Finished Goods – The items ready to be sent out of the factory.

- Work in Process (WIP) – When there are multiple stages to the product, WIP indicates the items as they’re worked into increasing states of completion.

Inventory shrinkage is when inventory is gone, but was not sold.

- Theft is the most likely way inventory goes missing, with damage being a close second likelihood.

- Theft is very difficult to manage and requires a combination of good hiring practices, locks, and security cameras.

- Inventory obsolescence is when it can’t be sold anymore (e.g., out-of-style clothing, rotten food).

One specific way to track the health of a business is through the inventory turnover rate.

- Tracking the time between each individual item being bought and sold (or at least an average across products) can detect issues with inventory.

- If it’s too high, shrink is almost guaranteed, meaning the company will lose assets.

- If it’s too low, any logistical bump could disrupt timely delivery, meaning the company will lose clientele.

- The easiest (and most intensive) way to track inventory is to use a perpetual inventory system that updates on every transaction (which typically needs computers with scanners to assist).

Liabilities

A liability involves anything an organization owes:

- Current liabilities are due within the next year:

- Principal and interest on loans in the next year

- Lines of credit with suppliers

- Wages owed

- Taxes payable

- Bank fees

- Non-current liabilities are long-term:

- Mortgage

- Pension obligations

- Principal and interest on loans beyond a year out

- Bonds and long-term loans

- Deferred tax liabilities

- Lease payments that aren’t due for more than a year

- Contingent liabilities are things an organization might owe.

One of the more frequent uses of accounting reports is to indicate assets a company can use to leverage/gear further financing.

- A company can have deficits and a negative net worth many times, but fails the first time it runs out of money.

Any money that needs to be put aside for a future liability is an encumbrance or provision.

- Sometimes, the money can go into a sinking fund to repay a debt or replace a wasting asset.

- The amount of unsecured debt a company owes if it’s liquidated is its subordinated debt.

A loan can be compound or simple interest:

- Simple interest loans charge periodic interest on the principal (e.g., an unpaid 3% on $100 is $103 on Month 1, $106 on Month 2, $109 on Month 3).

- A compound interest loan charges interest on the principal and interest (e.g., an unpaid 3% on $100 is $103 on Month 1, $106.09 on Month 2, $109.27 on Month 3).

- Compound interest is subtle, but over time it creates exponential (and some would say extortionate) costs on unpaid debts.

Accounts Payable (A/P)

Even if an organization stays very diligent to paying all its bills, an organization will always have some form of owed payments that are “payable” to other entities:

- Payroll (the most common)

- Alongside payroll, there’s also withholding for tax and benefits (e.g., health insurance)

- For convenient payroll calculations, 3 minutes is equal to 0.05 hours

- Outstanding loan principal or interest to be paid to other entities.

- Subscriptions which expect payment after delivery.

- Trade Payable, which is when a vendor has given goods or services but hasn’t been paid yet.

Often, not tracking liabilities can cause loans to go into default and further troubles for an organization.

Sometimes, charges need to be reversed, usually for defective goods or poor service.

- The Visa/Mastercard duopoly means many payments have guaranteed transaction fees.

- A chargeback is reversing the payment, which may still incur transaction fees.

- Rebates give a partial refund for services that were overpaid or partly used and then canceled.

- Credit notes cancel a customer’s debt.

Debts can be secured (with some form of collateral) or unsecured (with a promise and wishful thinking).

- Unsecured debt is essentially impossible for the lienholder to ensure it will be paid.

- While most secured debt is against the object in question (e.g., an automotive for an auto loan), it can be collateralized on essentially anything the lienholder will agree to, typically with a refinancing agreement.

Bonds

While anyone can borrow money from a bank, sometimes a company does not want to use a bank, so they’ll issue bonds instead.

- A bond is a specific debt instrument that allows large organizations like governments and corporations to borrow a lot of money from many people.

In its most straightforward use, a bond’s structure is relatively straightforward to understand:

- An organization issues bonds with an interest rate and maturity, typically in $1,000 or $100 denominations (e.g., 10,000 bonds at a $1,000 face value).

- Those bonds will have a certain number of years to maturity, with an interest rate (e.g., $1,000 face value, with a 4% yield to maturity in 3 years).

- The bond price will be whatever the investor originally pays (e.g., a $1,000 bond with a 4% yield to maturity in 3 years is $889).

- Before the bond matures, the investor can take back their money without interest.

- At the bond’s maturity, the investor can redeem that bond at any time, and the organization must make a balloon payment of the entire amount.

This gets much more complex, though:

- Some bonds are callable before the maturity date. In that situation, the yield-to-call will be lower than the yield-to-maturity (e.g., 1.7% instead of 4%).

- Bonds can be sold at par, but also can be sold at a premium or discount. This can happen from market conditions for the bond, as well as the reputation of the organization.

- The organization can use a coupon rate, which is where the organization pays a set percentage of interest every year (e.g., a 4% coupon rate on $1,000 pays $40 a year).

- If the coupon rate is the same as the yield rate, the organization will simply pay back the original amount when it’s called.

Like any other debt obligation, bonds can be secured or unsecured:

- Secured bonds collateralize an asset. A mortgage-backed security (MBS), for example, will collateralize the title of the borrower’s home.

- Unsecured bonds by companies are called debentures. In the event of a liquidation, unsecured creditors will only get whatever assets are left over after the secured investors.

Short-term bonds are 1–3 years’ maturity, medium-term are typically 10 years, and long-term are over an even longer period of time.

Equity

Assets deals with things that “exist”, and liabilities deals with things that are “owed”, but equity is strictly conceptual.

- Since investors often make decisions from optics (or are taken in by fashions they don’t understand), there are many complex domains within equity that have very little practical explanation.

- The only 2 ways to increase profits are to increase revenues or decrease expenses.

There are a few forms a business can take. They are either taxed before the owner receives money, or it’s pass-through to the owners:

- A sole proprietorship is a person’s individual business (pass-through).

- A partnership is the shared business of several individuals (pass-through).

- A Limited Liability Company or Limited Liability Partnership (LLC/LTD or LLP) is a legal (not accounting) demarcation to protect the business owners from liability.

- A corporation is a living, separate legal entity that’s incorporated on a specific date, and comes in a few forms:

- A C corporation can be publicly traded (not pass-through).

- An S corporation has many more filing requirements and can’t be publicly traded (pass-through).

In a publicly traded company, the shares are owned by whoever is willing to pay for them, and the majority stakeholder typically has decision-making power over the company.

A company can also perform a share repurchase, where it buys back the shareholders’ shares of stock.

Income

A company that succeeds in an accounting period will have money left over, and it has several options:

- Save it as Retained Earnings, typically by placing it in a reserve account (i.e., make a self-insurance policy).

- It’s taxable, but reinforces Operating activity.

- A not-for-profit organization can’t technically make a profit.

- Reinvest the money into more assets (e.g., buy new equipment).

- Often not taxable, and can be an Investing activity.

- Pay down liabilities.

- Not taxable, like a Financing activity, but boring to executives.

- Use the money as collateral to get more liabilities.

- Not taxable, a direct Financing activity, but exposes more risk to the company.

- Send the money out as Owner’s Draw (to the owner) or Dividends (to the shareholder).

- Taxable, and lowers the company’s net worth, but is how people who own the company get paid.

Calculating total earnings isn’t always simple:

- Gross income is the total earnings after subtracting loss from profit.

- EBITDA: earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization.

- EBITA: earnings before interest, tax, and amortization.

- EBIT: earnings before interest and tax.

- Net income comes after removing expenses, interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization from revenue.

- The quality of earnings is actual earnings that come from higher sales or lower costs, and can’t be attributed to accounting anomalies.

Expenses

Overhead is the cost of keeping the organization running that’s not tied to production or sales.

- The break-even point is the precise number of units that must be sold in an accounting period to return a profit.

- Quantity to sell = total fixed costs / (selling price per unit – variable cost per unit).

- An example helps the most to illustrate the concept:

- It takes $10,000 to run the organization in a given month.

- That same month, the company’s product can sell for $100 and costs $50 to make.

- If the company sold 100 units (making $10,000), it would cover the overhead, but not the per-unit price.

- To make a profit of $0, they would need to sell 200 units (10,000 / [100 – 50]).

Operating risk is when fixed operating expenses are high enough that they may interfere with profitability.

Paying Out

If the organization isn’t owned by a singular entity, the owners each own a percentage of the earnings.

- The company’s stock is a fractional “sharing” of that company.

- Preferred stock is paid dividends first and has priority with company assets (e.g., with a liquidation), but the shareholders don’t have voting rights.

- Common stock is secondary on dividends and receiving assets, but shareholders have voting rights.

- The rights to manage the organization are often not evenly matched with the income they’d receive (e.g., board members can’t own common stock).

Often, the language of the corporate bylaws dictate how stakeholders can be paid.

- Frequently, the leadership leaving can trigger a golden parachute, leaving that executive very wealthy even as they leave the organization.

Equity Games

A stock split divides the shares evenly (e.g., 2:1 or 3:1).

- This means every shareholder has twice or thrice the shares, at 1/2 or 1/3 the value.

- Nothing technically “changes”, but our bias means it can influence people to buy more stock.

For various reasons that affect equity, a business can be carved out into different domains:

- Some portions of a business are cost centers (often e.g., accounting, IT) and others are profit centers (e.g., sales, marketing).

- Segment reporting divides out various divisions of a business to create specialized reports.

While a dividend is considered income that goes to the shareholders, a share repurchase/buyback is considered an expense.

- Therefore, net income can be reduced by buying company shares back from shareholders.

The nominal value of a share, when it’s first issued, establishes its initial public offering (IPO).

- That IPO value will move around (meaning its value isn’t that utterly important, but it generally represents a dramatic shift in the way a company operates and indicates the first time the public can purchase it.

- The listing requirements for IPOs are a legal domain that falls way outside the range of accounting.

Stock Markets

The complexity of stock markets comes through a proliferation of third parties.

- Market makers are individuals or entities that arrange two-sided transactions to buy or sell securities and make a profit between the bid (buying) and ask (selling) price.

- The National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO) represents the highest bid and lowest ask for a security, making it the tightest bid-ask spread.

- Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) is a small commission the market makers make when

Valuation

Typically, valuations take more work than most standard accounting activities, so they’re made annually at most, or when needed.

- The measurement will be very specific when investors, governments, or equity-holders want to see it.

Estimations and reality don’t always match, and variance is the difference between them.

The book value is the lesser of the original cost paid for the asset (historical value) and its current value (fair market value).

- Sometimes, a buyer can pay a premium on top of the advertised price.

- Other times, the asset can be discounted.

Cost-based pricing determines the price of the sold good on how much it costs to manufacture, not on marketing.

- Typically, a highly competitive market requires cost-based pricing, and increasing profits involves cutting costs while maintaining the product’s quality.

One of the most severe procedures associated with valuations is when it goes bankrupt (or insolvent if it’s an LLC):

- All secured debt is reconciled first, typically by those organizations claiming their assets.

- Any remaining assets are liquidated to pay the rest, based on a specific order.

The discrepancy between the appraised net worth and publicly interpreted value by a company is often different.

- Gross margin is the difference between the cost of making/getting something and how much it’s sold for.

- Accountants only concern themselves with Fair Market Value (what its assets are worth, minus its liabilities) and Historical Value (what people originally paid for it), so they plug in Goodwill for the price will people actually pay for the company.

Ratios

There are tons of ratios, which take several numbers to create a third number.

- Most of the ratios can be useful to determine the health of an organization, barring Goodhart’s Law.

- Numerous ratios serve as key performance indicators, and new ones are constantly arising.

Ratios which measure profitability:

- Operating profit margin = operating profit / total sales

- Net profit margin = net income / net sales

Ratios that indicate how prepared a company is for short-term changes:

- Current ratio (or working capital) = current assets – current liabilities

- Quick ratio = (current assets – inventory – prepaid expenses) / current liabilities

Ratios that indicate long-term financial strength relative to debt:

- Debt ratio (or debt-to-total-assets) = total liabilities / total assets

- Long-term debt ratio = long-term liabilities / total assets

- Debt-to-capital ratio = total liabilities / (total liabilities + total equity)

- Debt-to-equity ratio = total liabilities / shareholder equity

- Fixed-charge coverage = EBIT / all interest and lease payments

Ratios that can indicate investment performance and profitability:

- Return on equity = net income / average shareholder equity

- Gross margin = gross profit / net sales

- Return on assets = net income / total assets

Ratios for multiple owners’ return on their investment:

- Earnings per share = total profit / number of shares

- Price to earnings (or P/E) = the market price of a share / earnings per share

- Can use the previous 12 months (trailing P/E) or projected 12 months (forward P/E).

- Price to book value = share’s market price / (share’s book value – intangible assets)

- Price to sales = price per share / revenue per share

- Dividend yield = annual dividend / share’s market price

Taxes

Besides the owners, the singular most universal interested party in an organization is the government of that region.

- For that reason, accountants spend a lot of time understanding the relevant tax code for their specialization.

- If you need one, a good tax accountant is typically worth what they’re paid, but a bad one will likely cost more than what you’ll save.

Unlike most other aspects of accounting, tax accounting can’t be dogmatic to the point of perfectionism.

- An item may sometimes be expensed entirely, or it might be depreciated as a long-term asset.

- Expense categories may vary depending on what an accountant can justify to a tax auditor.

- Equity has many variations within tax law, meaning it works like any other form of law (i.e., persuasion through logic).

- The only requirement is that whatever the accountant is doing stays consistent across periods.

Most people do not need a tax accountant to file their taxes.

- Essentially, you don’t need an accountant and can simply use software for the following:

- Employment wages (W2)

- Miscellaneous independent contractor work (1099-MISC)

- Interest income (1099-INT)

- Dividend income (1099-DIV)

- However, if your situation is any more complex, hiring an accountant is almost essential:

- Complexities involving trusts (e.g., corporations) or inheritance.

- Cryptocurrencies, foreign income or any other semi-regulated or unregulated investments.

- You run your own business.

Property taxes

Property taxes are assessed ad valorem (according to value), usually yearly.

Realty – buildings or land

- Buildings can depreciate, but land can’t.

Land value tax (LVT) – tax on the market value of the land itself

Non-realty (personalty) – jewelry, cars, business or intellectual property

Transaction taxes

Transaction taxes are during a period when there’s an exchange of property between parties.

Excise taxes

- Excise taxes are set on specific items to “cut off” people from using them.

- The most frequent excise tax is a 20% early withdrawal penalty for using money from a qualified retirement account before retirement age.

Sales tax – set on the seller

- Sales taxes are set on the seller, though the seller can add the price into the product.

- Use tax is sales tax from a different state.

Value-added tax

- For buyers, a tax on the purchase price.

- For sellers, a tax on the value they increased the product that was sold.

Gift tax

Taxes on transfers at death

- Estate tax is set against the estate of the deceased.

- Inheritance tax is set against the recipient.

Employment taxes

Except for self-employment, most employment taxes are pulled out of someone’s paycheck automatically and filed quarterly with the government:

- Social Security

- Medicare

- Unemployment tax

Most people below a modest income threshold receive a refund at the end of the year back from the government, which creates the ironic consequence of them being grateful to the government for their already-earned money.

- This compounds as well because there are certain tax credits (e.g., EITC) that give more money back to workers than they paid to the government.

Income taxes

The US Federal income tax system has a complex, specific formula:

- Income minus exclusions give Gross Income

- Gross Income minus certain deductions give Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

- AGI minus standard/itemized deductions and personal/dependency exemptions give Taxable Income

- Taxable Income references to the tax tables to calculate Tax Owed

- Tax Owed minus tax credits, previous pre-payments, and withholding gives the Tax Due/Refund

Tax tables use a progressive tax bracket system:

- An example:

- up to $10,000 = 5%

- $10,001 to $25,000 = 10%

- $25,001 to $45,000 = 20%

- over $45,000 = 35%

- A $56,000 Taxable Income will pay:

- 5% on $10,000 ($500)

- 10% on the next $15,000 ($1,500)

- 20% on the next $20,000 ($4,000)

- 35% on the last $11,000 ($3,850)

- Total Tax: $9,850

US State and Local income tax are adapted calculations off Federal.

Certain situations can increase the likelihood of a tax audit:

- Very high gross income

- Self-employed individuals with substantial business income and deductions

- Taxpayers with prior tax deficiencies

- Businesses with a large proportion of cash receipts

Many, many business expenses can deduct from taxable income:

- Advertising/promotion

- Alimony-related legal fees

- Automobile and transportation expenses

- Bank charges

- Commissions and sales expenses

- Consultation expenses

- Credit and collection fees

- Delivery charges

- Dues and subscriptions

- Employee benefit programs, including pension and profit-sharing plans

- Equipment rentals

- Factory expenses

- Gifts (to an extent)

- Home office

- Insurance

- Interest paid

- Internet domain names and hosting

- Job search expenses

- Laundry

- Licenses

- Maintenance and repairs

- Meals and entertainment (somewhat)

- Moving expenses

- Office expenses and supplies

- Payroll, contract labor, and consulting

- Postage

- Print and copy

- Professional development and training

- Professional fees (e.g., accounting, legal)

- Promotion

- Rent

- Salaries, wages, and other compensation

- Security

- “Service fees” (for not-so-legal activities)

- Small tools and equipment

- Software

- Supplies

- Taxes

- Tolls

- Trade discounts

- Travel

- Utilities like telephone, internet, and electricity

Though it’s sometimes more complex, other write-offs and write-downs can offset tax expense as long as they’re in the same tax year:

- Depreciation on assets

- Amortization or expiration of intellectual property

- Bad debt

- Charitable contributions

- College or trade school

- Continuing professional education

- Government bond dividends

- Losses on sold securities

- Prior-year losses

- Prior-year taxes paid

- Reinvested dividends

- Renewable energy credits

The US income tax code is configured to socially engineer a specific set of lifestyles:

- Employees > Entrepreneurs

- Teachers > other careers

- Going to college > skilled trade

- Maxing out retirement account contributions

- Parents of 2–3 children who stay home and go to college

Other Taxes

Government customs taxes set on foreign goods:

- Duties are indirect taxes charged to organizations, who then pass it on to the customer.

- Tariffs are direct taxes against specific things.

- Before the US income tax, most of its income was from tariffs.

Franchise tax is set against corporations.

Occupational fees are set as trade-related requirements.

Carbon taxes are against productive activities that generate carbon.

- Sometimes, a government can grant carbon credits, which can be exchanged as a commodity between companies based on need.

Tax Games

Any tax payment is a completely sunk cost, so anyone who can explore tax advantages will try to avoid taxes.

- Tax planning is usually best during low-income years, where a net operating loss (NOL) can be carried over into future years.

Increasing expense (and therefore reducing income) is the easiest approach to save on taxes.

- Substitute salary for stock options.

- Donate to charitable corporations (which may include political parties).

Tax shelters are government-approved domains that protect from taxation:

- Qualified retirement accounts (e.g., 401(k) or IRA).

- Qualified retirement plans (e.g., pensions).

- Government bonds, along with their income.

- Real estate, in some situations.

Tax treatments aren’t technically “accounts”, they earmark assets to specify unique ways to tax them, and most individuals have a very specific ideal order they should max them out:

- Anything up to the match an employer gives, such as 401(k) and IRAs.

- An employer match contribution immediately doubles everything invested into it.

- Tax-deferred treatments:

- Taxing the assets when withdrawing them means constant trades without any tax risk, then paying taxes before using it.

- This is ideal when you don’t expect a dramatic increase in your income.

- 401(k)’s/403(b)’s are through a corporation or non-profit/government.

- The options are specifically limited for employees (about 20 or so).

- Never borrow on a 401(k) or you’ll be hit with a ~40% loss when you leave the company.

- If the options are limited, look beyond that plan for your investing needs (such as an IRA).

- If the match is very low (such as 1%), its fees may make it an unwise investment.

- If the company doesn’t match the contribution, use an IRA instead to save on fees.

- When leaving a company with a 401(k), always perform a rollover into an IRA.

- Taking the money home will tax it when you cash the check.

- Your choices are limited if you roll it into another 401(k).

- Calculate if it’s worth converting to a Roth IRA.

- A 457 is similar to a 401(k), but for government and certain non-government entities.

- IRAs (Individual Retirement Arrangements) are a tax treatment that can apply to nearly any type of investment.

- They have a bit more range of investment vehicles for investing than other arrangements what you can invest into.

- If you have an earned income, you can have an IRA.

- SIMPLE IRAs are funded mostly by an employer.

- SEP IRA plans (Simplified Employee Pension) can be set up with any business, even self-employed.

- 529 Plans are meant to save for college.

- Only use a 529 that leaves you controlling your account all the time.

- After-tax treatments:

- Taxing the investment beforehand means the returns aren’t taxed (e.g., Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)).

- This is ideal if you’re making less than when you’ll retire.

- If a parent, consider the Coverdell Education Savings Account (ESA).

- As long as the money pays for college or education-related expenses, withdrawals don’t have any tax liability.

- Never buy an ESA that freezes options or automatically changes the investment from the age of the child.

It makes sense to hire someone for work, such as a family member.

- However, they must do some sort of work, or it’s a no-show job.

One simple method is to geographically route business activities to the most tax-advantaged locations.

- Rent an office in another state and make it the company headquarters.

- Move operations to other countries with little to no tax for those activities.

Many governments provide capital allowances and tax credits for specific activities.

- Specific, fashionable industries and activities tend to receive tax credits.

- Lately, energy-efficient and “green” activities have received plenty of government grants and advantages.

If an organization is savvy enough and has enough startup costs, they can create a not-for-profit charitable organization with a board run by hand-picked people loyal to their founding organization’s leadership.

- Whenever a company is about to experience significant tax expense, they can make a charitable contribution (typically at the end of the year before the end of December) that offsets tax payments.

An Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) is an odd domain that allows completely tax-free transfer of company equity:

- Convert an existing, profitable company into an S corporation with company stock.

- Create an ESOP trust that can own company stock.

- The ESOP trust acquires a debt from the company, then purchases a giant chunk of the company (or all of it) from the owner, making it an S corporation owner and the company owner wealthy.

- Every year:

- The company does a stock valuation of itself.

- The ESOP administrator tracks everyone’s income as a percentage of total payroll expense.

- The company makes a predetermined contribution to the ESOP, which it immediately uses to pay off some of its debt to the company.

- That debt payment releases a fixed number of shares to a suspense account.

- The shares are evenly distributed into the employees’ retirement accounts.

- When the employees reach retirement age, the shares are converted into cash and distributed (typically in installments).

- The employees’ former shares that were converted are redistributed, just like in Step 8.

- If the debt is ever fully paid-off, the ESOP acquires another loan from the company.

- As long as it fulfills the requirements for a retirement plan, the company is owned by its employees while they work there.

Wealthy individuals have several progressively more favorable routes to reduce taxation:

- The conventional means of reducing wage income, then receiving income tax on the remainder.

- Strictly receiving company stock as income, then selling the stock and paying comparatively lower capital gains tax on it.

- Strictly receiving company stock as income, then using the stocks as collateral to borrow money, then spending borrowed money (which is untaxed) while still receiving unrealized capital gains.

Even then, tax evasion is a frequent practice:

- Migrate money in between a vast network of banks to hide the record, often across national boundaries.

- Involve many associates who serve as board members of various entities.

- Use accounting across multiple nations, and with different legitimate accounting standards each time.

Auditing

Audits are an extremely mind-numbing process of examining an organization’s entire accounting system.

There are 3 types of audits:

- Internal audits – company employees examine issues with financial and business practices.

- External audits – independent evaluators examine financial records to provide an objective opinion that affirms their financials are accurate and complete, or offers guidance to help them make more informed financial decisions.

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits – financial examinations conducted by the IRS to ensure tax was sufficiently paid.

Irrespective of whom, the process is straightforward:

- Start with the first accounting period to audit.

- Start with the first account.

- Grab a sample transaction from that account.

- Thoroughly examine the sample transaction and all supporting evidence.

- Ensure the transaction has material evidence and is accurate.

- Repeat Step 3 a few more times.

- Move to the next account and repeat Steps 3-6.

- Repeat Step 7 until all accounts have been audited.

- Move to the next accounting period.

- Repeat Steps 2-8 for that accounting period.

- Repeat Steps 9-10 until all accounting periods have been audited.

Auditors are hunting for specific things that may represent worse problems:

- Compensating errors – two mistakes that curiously canceled each other, since it may belie worse problems.

- Creative accounting – clever methods that make accounts appear like the balance is higher or lower than they really are.

Underneath all of it, auditors work to expose unethical or criminal activity:

- Fraud – intentionally misusing a company’s resources.

- Money laundering – hiding illegally obtained money by merging it in with legal activities.

- Negligence – disregarding the rules or failing to exercise proper care in keeping records.

Auditors, like claims adjusters, do not believe in mere coincidences, and they will issue an opinion after their investigation:

- Unqualified opinions indicate that the information is sound.

- Qualified opinions indicate they have a “qualification” that demonstrates a problem with the information.

There are also specific audits for ESG and cryptocurrency, but they’re new enough trends that there’s not as much precedent as a standard audit.

Mergers/Acquisitions

Generally, a company that isn’t growing is dying, and they grow through several approaches:

- Growing larger and expanding their operations, which will reflect somewhere on their financials.

- Acquisitions of other companies, though they themselves may grow larger as a unit of a larger company acquiring them.

When a company is purchased, the relationship between the entities gets complicated.

- A merger combines the accounts together from two entities to form a singular, separate third entity.

- An acquisition keeps the accounts separate, with a parent and subsidiary company.

- A consolidation combines all of a subsidiary company’s accounts into a parent company, and shares being exchanged in a stock-for-stock merger.

- Consolidated financial statements track all activities of a parent company, along with its subsidiaries.

Most of the issues tie into conflicts about company valuations, along with the rights and privileges that naturally emanate from the forms of the final business entities from the procedure.

Beyond the value of an asset (which may have sentimental value for some investors), there’s a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) that diminishes the simple value of something:

- New software

- Installation costs

- Transition costs

- Employee training

- Security costs

- Disaster recovery planning

- Ongoing support costs

- Necessary future upgrades

Merger Games

An IPO is pricier and more complicated compared to a merger/acquisition, so a relatively new vehicle for companies is to create a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC):

- Someone creates a corporation that’s publicly traded, but with zero assets or liabilities.

- Its $0 or negative IPO net worth is therefore tax-free.

- People will trade that IPO on a market based on their understanding that the company will purchase other companies.

- After the first accounting period or tax year, the company purchases other companies.

- Those other companies were privately held, but are now part of a mega-merger with other companies.

- After a few purchases of those other companies, the corporation operates like any other corporation.

- The legitimate value of the SPAC is based on the performance of those other companies, give or take how well they were managed during the entire time up to that point.

- SPACs are particularly popular among industries that lean heavily into intellectual property, such as software or pharmaceuticals.

Breakups

A company can sometimes become too large. At that point, it may need to break up:

- The company has too much bad publicity and needs a new brand.

- The leadership had a difference of opinion, and they agree to segment the company internally into several subsidiaries.

- A government considers them too large as a monopoly, and uses laws to break them apart.

However it happens, the accounting typically records the information as at least a partial liquidation of the original entity, then the formation of a new entity.

Accounting Fraud

There are many ways to violate GAAP and lie on accounting reports.

Money laundering involves moving money across multiple entities to make the accounting appear legitimate.

- Income must be overstated (to move money in).

- Expenses must be proportionately embellished (to move money out as well as avoid the risks of a tax audit).

Losses that should be indicated as expenses can easily be obscured as future losses if the liabilities aren’t closely tracked.

Using shell companies offloads expenses or revenue onto subsidiary companies.

- The concept is relatively simple:

- Create a subsidiary organization.

- Pass on all expenses to that organization.

- The publicly traded entity will make obscene profit, creating an investing boom (e.g., Enron).

- This can also be reversed to avoid taxation, with shell companies in more tax-favored situations receiving the revenues.

In unregulated cryptocurrency, traders can use wash trading (inspired by wash subscribing in marketing) to magnify the value of their assets:

- Make a cryptocurrency that mines across at least a few servers.

- Perform many, many trades (often with fees) with yourself, which makes it look wildly popular.

- Advertise to as many people as possible that your cryptocurrency is wildly popular.

- If you can acquire enough actual users, you’ve created a legitimately popular cryptocurrency and can sell your assets for actual cash.